The Museification of Language

Should languages be preserved?

Edited in June 2025.

Introduction

I’ve often spoken about the difficulties with what we could call “archivism”: the tendency in our time to preserve every relic of the past and to allow nothing to be lost. By contrast, when our ancestors dug up a barrow or looted an ancient ruin, they threw out anything they couldn’t use: everyday artefacts that we would put on display in museums and would fetch high prices were discarded without a second thought. This attitude might appal us, but a lack of preoccupation with the past arguably belongs to a more living culture, not hung up on old glories.

It’s a tricky one because anyone with any feeling for history or civilisation in general will agree that we must keep our heritage intact and not allow the beauty of the past to be swept away, especially by an age that produces nothing beautiful itself. The flipside is that it’s not inconceivable that a precondition for the emergence of something beautiful or youthful might be the destruction of our “botched civilisation”,1 as I’ve touched on ad nauseam.

When it comes to language, we’re not just dealing with “two gross of broken statues” and “a few thousand battered books”,2 though, or any inanimate relic, but with the most living phenomenon of all. Human beings are “sayers”;3 an enormous part of our being is found in language and lived through it. When we demand that language be preserved this isn’t just a matter of putting a material object behind some glass, but entire cultures and groups of people. If we want someone to speak some obscure indigenous language from Lalapaloolazekistan, because it’s like … an authentic vibe, man, we’re more or less asking them to cut themselves off completely from economic opportunity for the sake of our subjective, far-removed tastes. Of course, the global civilisation that desperately works (through bodies like UNESCO) to maintain “endangered” languages, is responsible for their decline in the first place.

Even well established national languages look worriedly at the increasing Anglicisation of their vocabulary as English becomes the world’s Lingua Franca. Like any attempt to get traditional or natural outcomes through modern means, these projects are inherently incapable of providing what they aim to. Archivism cannot create what it wants to preserve and the traditional mindset cannot preserve what it creates.

Language and Identity

National languages are artificial creations. At least - their national status is. Nation states, though preexisted by the ethnic groups that they represent, arose as a codification of identity around the state. Identity as nationality is something imposed rather than received, even if it does stem from something that organically exists. In an effort to solidify emerging nationalities, centralising governments have for centuries pushed towards linguistic standardisation and regional languages and dialects have been ever more marginalised in the process.

For me and many others, the favourite case study in this is Italy. The native Romance Languages form a “dialect continuum” across Europe; neighbouring regions differ slightly but the further you travel the less able you are to understand the local decendant of “Vulgar Latin”. That left the Italian Peninsula with a great north-south linguistic gradient, with identifiable groupings dating back to the Middle Ages.

These are not local varieties of what we know as “Italian”, though of course those do exist too, and are influenced by the “autochthonous languages”4 of each region, but are best understood as completely different languages, rather than “dialects” of Standard Italian, which descends from Tuscan, one of the languages of Italy. The Risorgimento took the neat literary language of Florentine tradition, which only a tiny elite of about 2.5% of people spoke outside of Tuscany,5 and made it the official language of the new Kingdom of Italy. Within a few generations, everyone from cheesemongers in Bergamo to Apulian peasants had the language of Dante on their lips… though not always with the same eloquence.

Like everywhere, provincial dialects are often associated with low status in Italy. Very few people speak their “dialetto” exclusively anymore, and if you can speak one at all then you’re likely older, lower income and less educated than those who only speak Italian. It’s also worth saying also that dialects like Neapolitan and Sicilian happen to be associated with certain subcultures but more importantly, with regional identity.

Being “provincial” has a real impact on identity. When the prestige language variety of your country; the language of economic and social opportunity, is not your own, you’re permanently on the outside to some degree. Part of the reason that these dialects have declined so rapidly in the past 100 years is because they lock you into social and economic stagnation; there’s no motive to learn them beyond regional pride and a kind of identification against the moneyed, the higher-status and those closer to the seat of cultural prestige. If we take Naples as an example, although Standard Italian is increasingly used in a daily context, the use of the local language is relatively robust compared with Northern Italy, partially due to the strength of local identity which is reinforced in opposition to Northern Italians who look down on them as Terroni “peasants”. In A New Philology I quoted Irish poet Michael Hartnett’s description of English as a “[...] necessary sin; the perfect language to sell pigs in”,6 this applies nicely to the Italian context too.

People are left with two options: doubling down on their local identity which means embracing something associated with low status, or trying to escape it altogether and adopting a more metropolitan and “refined” way of speaking that will grant them socioeconomic advantage. As we see in this clip from the drama Gomorra:

Gomorra (S03 E02)

There’s even an animosity shown towards those from one’s own region who modify their accent. It’s seen as slimy, fake and inauthentic; like they’re ashamed of their roots. Non-standard speech is not inevitably received as low status in every context, however. If we compare economically impoverished Southern Italy with wealthy Catalonia, although there is a similar situation in that learning Castellano is a must for employability, Catalan is in no way a “low-status” language, even after being banned in schools under Franco. Likewise, there’s a difference between Scottish, Welsh and Irish nationalism, (which, like Catalonia, lean heavily into a sentiment of resistance against a domineering other) and a purely regional identity like that of the North of England. The English North-South divide is a division within an ethnicity, not between, but no less concerned with status. If we compare an Edinburgh accent with a Glaswegian one - or for that matter with a Northern English one, we can see that status connotations are if anything secondarily to do with nationality.

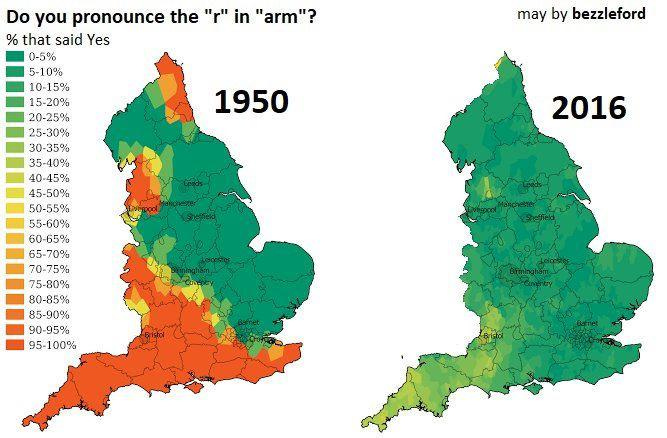

We also observe the interesting phenomenon of urban dialects among the non upwardly mobile portions of society actually intensifying in the UK against the general trend of convergence. This is taking place with London’s MLE accent, but also among native Britons in Liverpool, Glasgow and Swansea. There’s a sense here of identifying against the cultural mainstream. Regardless of the motivation; ethnic, regional or socioeconomic, people are concerned about holding on to their linguistic particularity in the face of standardisation. What’s more, people with no connection to that context whatsoever are keen to see them preserved also, as we will explore.

Quality and Quantity

I’ve tried to stay descriptive, but as with almost any discussion of linguistic homogenisation it comes with a not so hidden sense of remorse. To describe this process at all seems to be to lament it.

It’s often more explicit than that, even. The comments on pop-Linguistic edutainment videos on YouTube about obscure, declining language varieties are always full of cries of “we should preserve x” obscure language. Of course, it goes way beyond that. Grand bureaucracies have been charged with promoting and sustaining the use of “endangered” languages throughout the world, to varying success. The beauty of each unique mode of human expression cannot be allowed to vanish!

There’s an inconvenient hypocrisy in this, however. Broadly speaking, the camp that opposes the imposition of national standard languages does so on the grounds that it is “prescriptivist”; saying how language ought to be, rather than “descriptivism” which aims only to describe it. Smug, self-labelled descriptivists scoff at the idiocy of seeing one way of talking as “superior” to another, but then go on to express an aesthetic preference of their own towards minority languages in promoting their preservation, which according to their own criteria makes no sense. They often denounce institutions like L’Académie Française for their efforts to preserve the “Frenchness” of French against Anglicisation, seen as arbitrary and unnecessary. To quote from A New Philology:

The [scientific-linguistic] orthodoxy would have it that all human languages are essentially equivalent, just with arbitrary and inconsequential differences in the sequences of phonemes that they use to say the same thing. This leads pop-linguistic types to sneeringly deride “linguistic prescriptivism”, the holding up of a “correct” standard form of language, typically in terms of grammar. Your Secondary School English teacher telling you off for saying “less” instead of “fewer”. If all language is essentially equivalent, no one way of saying something is any “better” than any other. So long as the listener understands the speaker, we’re told, who cares how it is said?

This conclusion is utterly unsatisfying, not just for me, but it ought to be for those making it also. First of all, who among us talking-creatures actually feels this to be true? Linguists, even more than the rest of us, are undoubtedly lovers of the richness of language and they themselves will lament the disappearance of endangered languages, or their suppression in favour of a national standard language. But, if all language is the same and there’s no legitimacy to “prescriptivism”, then why does it matter? When all is just an arbitrary group level aesthetic choice, what difference does it make? This is the forgetting of philology in its truer sense as the love of words.7

If you oppose the homogenisation of language then you are being prescriptive, which means that language is not all interchangeable and equivalent - it either matters or it doesn’t.

Let’s say that Roadman English has been abruptly banned in all British schools and conduct an interview with Callum, my convenient strawman and Exeter Uni dropout, on the subject [question marks used to indicate uptalk]:

“Mate like what the actual fuuhck? They can’t do that?”

“Why?”

“Becuz, you know, like, no one accent is better than any other? Like it’s all the same?”

“Then why does it matter if they lose their accent, if it’s all the same?”

“Becuz … you know, it’s like … maaate. That’s their language and like … their culture?”

“So one culture is more valuable than another?”

“Maaate-.”

At this point in the conversation Callum malfunctions and has to be sedated.

Now, I’m not saying it isn’t a tragedy that linguistic diversity is vanishing, but the only way you can be consistent in this position is in embracing a qualitative view of language. Every language, dialect and accent is qualitatively distinct. Scientific reductionism cannot account for this, since all languages can convey the same “information”, but we hear and feel each way of speaking to be its own. How someone talks tells you things about them; why else would people adapt their speech according to social circumstances. This is not an artificial process. We have instincts for a reason and the heuristic of how people talk is an early giveaway. You can be wrong in your assumptions, but it’s much more dangerous to assume everyone is the same than that they’re different. Status is at issue here but also familiarity, identity and difference more broadly. This is what underlies the linguistic pride of Catalonia, Wales or Naples. A qualitative sense of who they are, expressed in their language, is at issue. The thing is, that’s exactly the same as what underlies a belief in there being a “correct” way of speaking English. It’s no less valid than wanting to hold on to regional dialects. It’s an aesthetic standard that a group of people holds for reasons of identity, and I would argue it’s a valuable (and inevitable) thing for a civilisation to have prestige varieties of speech.

The scientific-linguistic perspective, that would uphold these languages and dialects simply in opposition to the very idea of preference, cannot account for this at all or justifiably associate with the preservationist perspective. The preference might not be around some inherent and quantifiable property but that doesn’t mean that the qualitative distinctions aren’t real and important and that people don’t prefer certain ways of speaking over others. In other words: we’re all prescriptivists - and that’s ok!

Words Behind Glass

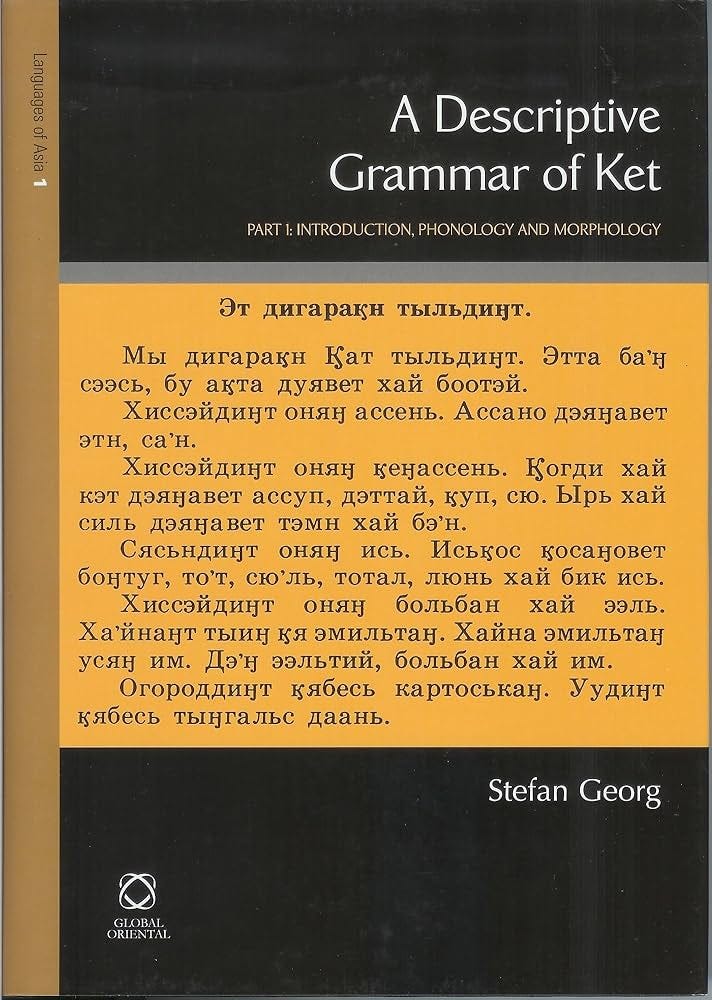

So now we’ve dispensed with the nonsense of seeing language in quantitative terms, we can embrace what actually motivates human beings to care about it, even from afar. I’m as guilty as anyone for seeing obscure or fading languages as darling antiques or rare butterflies in need of some charitable action to keep them going. Of course, for the actual speakers of a language, it’s something different entirely. Ket is a fascinating language spoken in central Russia by around 100 people, notable as a member of the only known language family that is native both to Eurasia and the Americas. Naturally, this has led to a lot of interest in the Ket language, first of all from the linguists who made these discoveries through their documentations of it.

Ket is, unsurprisingly, classed as “severely endangered” by UNESCO. In today’s world, it’s utterly useless in economic terms, and need is a lot of what motivates language learning. We would like to think that people would assiduously cling to their mother tongue out of sheer pride, but this is a romantic sentiment that appeals to us from a completely disengaged standpoint, offering little to real people and their real lives. People do preserve their customary languages, but there comes a point when a language has to be needed to survive, without being kept alive on the dime of Western sentimentality and refusal to see anything perish.

The engine of industrial civilisation, having gone from national to global, drives this all ahead, but with a guilty conscience. Some of the remit of control that Western Man feels himself to have is redirected towards preserving older “authentic” forms that sprang from the organic world that his artificial one continues to replace. Like at the reservation in Brave New World, the civilised can gawp and admire the primitive as entertainment. Likewise disappearing languages become a little pet project for distant enthusiasts. Their continued life is for philanthropy; linguistic life-support. As I’ve said time and again, something can only exist authentically if it does so from necessity. So long as these languages exist by the grace of a system that would, left to its own devices, see them extinguished, they are caged pets; their dignity and actuality robbed from them; not even allowed to die.

In fly the categorisers and taxonomers, calipers in hand. They press the native dry for his words, which they fling out into great constellations of “grammar”, never identified, never thought of, never pointed out before. This they then call “the language of the tribe”, and insist it be drilled into the youngsters, who are already forgetting the mother tongue. None speak it when they go to town. A chimera, exhaustively collated and standardised is thrust in their faces in printed letters invented on their behalf. The spirit of the elders does not walk among the black pillars on the page. They have turned the spontaneous voice of the tribe into an inferior copy of the language of money. The very quality that they came to preserve has evaporated in the process.

In doing so, the linguists make a reality of their theory - that all languages are essentially equivalent. An unwritten, uncategorised and unrecorded language evades quantification - it exists only in quality, since it has not been “created” on the grid - in the treatise or wikipedia article.

I can denounce this “museification” all I like but I cannot say in good conscience that I am not an example of exactly what I am critiquing. Linguistics fascinates me and the data and taxonomy around it also. I also hate to see any diminution of the variety and diversity of the world; it really is like a species going extinct. A language is a whole world - when one dies, a whole plane of being is gone forever.

Everyone has their linguistic tastes and there is something about Neapolitan in particular that captures me. I saw not long ago an Instagram post8 from an account promoting La Lingua Napoletana that encouraged the adoption of a standardised orthography and spelling convention for the language, to assist in its being taught and used in more formal contexts. In classic foreign-enthusiast style, I thought this was an atrocious idea. The whole quality of Neapolitan, in my eyes, is exactly in its vibrancy, vividity and unselfconscious vernacularity (and yes I realise that I sound like a middle aged American liberal talking about African art). The fact that people spell it in a million ways, without care for rules, is so much a part of its appeal. If you gave it all the trappings of a National Language™ you would make it just as artificial as what is replacing it.

I stand by these claims, but this does nothing for the native speaker. I used the word appeal - that’s only something that matters to me. An actual speaker of the language wants to use it now; today; in a modern, practical context. In a weird paradox, my desire to keep it “authentic” and not make it into a rigid, standardised and chartered language, is itself a desire to place it under a kind of protective lid for my own admiration and tastes.

In order to actualise themselves and live beyond a sequestered existence in the linguistic zoo, threatened languages need to ape the behemoths that replace them, losing their qualitative spontaneity in the process. It seems that the only way for these languages not to lose themselves would be to let them die. Unsurprisingly, this is not a popular position.

Letting Language Be

So what’s to be done? I have a tendency to let readers down in this area; I love to diagnose and never offer solutions. Hey, I guess that makes me a descriptivist after all.

Like with any conservation effort, I can’t really bring myself to full-throatedly denounce the preservation of endangered languages, even if there’s a part of me that finds it worse than letting things die. As I said in Control Paralysis, the power to determine life and death actually forces us into always prolonging the existence of people, or in this case things, regardless of the unanswerable question of whether they should.

I suppose all we’ve learned is that the being of language, like everything else, is challenged in modernity. I will reiterate my call from the earlier article for a new philology. We must rediscover a love for words - like we must rediscover a naive and unexamined wonder for the world as a whole. The quantification of language is not a value-neutral process, but like with all Technique, it crushes the spontaneity of what it represents and thrusts the copy in front of the original - as if the model were the true being and the uncatalogued spoken word itself were not.

A rare, indigeneous language is like folk music; as soon as it is recorded, it evaporates. In recent years I’ve increasingly come to dislike folk recordings. Folk music is itself when it springs into life spontaneously in a pub corner, or when generations iterate and vary on inherited themes. As soon as you freeze it into an artefact, you kill it. It suddenly becomes just like any other recorded music; the popular “mass-music” that drove folk music to near extinction - that undid and replaced its organic place in culture. The correspondence between this and the decline of regional languages is clear.

The tragedy of this conversation is the realisation that the efforts taken to “rescue” something from the consuming tide of modernity - the “action” we might take - is itself a reification of those same modern conditions. Once a dialect, a folk tradition, or any custom is seen as up to us to decide the fate of; once it becomes a recorded fact to promote or preserve, it has already vanished as it once authentically existed. Ironically, something is only truly authentic, when no one is asking about whether it is or isn’t “authentic”.

A proper love of words will let language be, rather than look to quantify it and turn it into an object of admiration and assessment; we may embrace it as it is. Perhaps, rather than obsessively recording all traces of these languages so that when the last speakers die they will leave an abstracted footprint totally alien to the true context of their existence, we should joy in the knowledge of their being spoken at all and allow them the dignity of dying gracefully, undisturbed by the operating tools of the linguist. But then, who am I to say?

Pound, E. Hugh Selwyn Mauberley.

Ibid.

Heidegger, M. Introduction to Metaphysics, p90.

Tamburelli, Marco. (2010). The vanishing languages of Italy.

Ibid.

Hartnett, M. A Farewell to English.

Lindsey, M. A New Philology.

Which I would try and locate but I have since deleted IG.

The Quebec Office for the French Language takes the approach of suggesting terms of French origin to replace English terms that people use every day. If their suggested term sticks, it becomes the standard, and if not, they acknowledge that people use the English term and accept it. It seems like a good balance between being descriptivist and proscriptivist, or at least the best workable balance.

I never before thought about how artificial are the connections between symbols and sounds. In formal logic and mathematico-computer-y approaches to natural language you absolutely never get this approach, that I've seen at least. Even rigid adherence to standardised grammar and spelling turns out to be "technique", more legacy of the 20th century masquerading as natural law. Thought provoking piece, thanks.